- Home

- Ricarda Huch

The Last Summer Page 2

The Last Summer Read online

Page 2

Lyu

JESSIKA TO TATYANA

Kremskoye, 10th May

Dearest Auntie,

You’re perturbed by our protector, who is here specifically to give us reassurance? I am entranced by him and my letter reveals a suspicious gaiety? Goodness gracious, of course I find him agreeable; his presence has allayed Mama’s fears! Don’t worry, dearest Auntie, if he should fall in love it will be with Katya, and I’m sure you don’t consider Katya’s heart to be as fragile as my own. Or are you concerned that Peter might become jealous? Do you know what? I believe that Katya doesn’t really fall in love seriously; she sits with Velya amongst the redcurrant bushes and the two of them eat with the same rapidity they did ten years ago, as if they were going to be awarded a medal for their feat.

Truly, Mama is calmer and happier than she has been for a long time. Good God, when I think back to how she was those last few days in town, the performance she would make if Papa stayed out half an hour longer than she expected! Recently she couldn’t find him in his room, nor anywhere else in the house and not in the garden either. She was already starting to get jittery when Mariushka told us that the governor had gone for a walk with his secretary. At once her mood settled and she asked me to join her in a duet, claiming that I sang beautifully, and belting out the tune herself like a nightingale in a romantic novel. This afternoon Papa was still a little drowsy when he was called for tea. Mama picked up her lorgnette, looked at him closely and asked tenderly, ‘Why are you so pale, Yegor?’ Papa said, ‘Finally! I thought you didn’t love me any more because it’s taken you eight days to ask.’ He was teasing her, of course, but if Mama’s anxiety, which he always jokes about, were to vanish, he would actually feel neglected. This is what the governor is like.

It’s just occurred to me, dearest Auntie, that I have no idea whether your cold has gone for good, nor whether the mysterious, awkward pain in your little finger has subsided, nor whether and when you are coming. The lilac is blooming, the chestnuts are blooming, everything that can bloom is in flower!

Affectionately, Jessika

VELYA TO PETER

Kremskoye, 12th May

Dear Peter,

If you let your jealousy show, you’ll make yourself look ridiculous in front of Katya. And what for? To begin with you might still be jealous of me, but you’re not refined enough for that. Lyu is courting Jessika – that’s to say he gazes at her and commands her with his eyes, for of course she falls immediately for this. Lyu is an extraordinary man, soulless, you could even say, if it’s possible to use that word to describe an element that is pure force. I expect he would have no qualms about making Jessika unhappy, or any other girl for that matter. If you have the courage to abandon yourself to him completely, you also need the courage to allow yourself to be destroyed. And why do the girls dive so eagerly into the light? Whatever the reason, it is their own decision, like with the moths that burn their wings. Moreover, Lyu would never sacrifice a girl to his vanity, as most of us do. He only destroys them incidentally, as the sun does. They mustn’t get too close to him, but of course they cannot stop themselves. Katya is, thank God, different, which I love about her, although I shouldn’t want all girls to be like her.

Yesterday Katya and I discovered a Turkish confectioner in the village, who had the most wonderful wares: red and sticky and translucent and rubbery. He seems to be a real Turk, for I’ve never eaten anything so sweet before. I imagine the further south-east you go, the more wonderful the sweets become. Katya and I kept eating; the Turk was expressionless as he watched us with his large cow-like eyes. Eventually we couldn’t eat any more and I said, ‘We’ve got to stop now.’ ‘Don’t you have any more money?’ he asked; I fancy he regarded us as children. I said, ‘I feel sick.’ His yellow face remained unmoved. Had we exploded before his very eyes I doubt he would have so much as twitched.

We met a very lovely girl in the village with whom we used to play when we were children. Back then we found her awfully ugly because of her red hair, which we would tease her about; now I found her devilishly nice. I called out to her, ‘Anetta, you’re not ugly any more!’ She immediately retorted, ‘Velya, you’re not blind any more!’ I couldn’t take it any further as Katya was there, but I gave her a nod and she understood me.

Velya

LUSINYA TO TATYANA

Kremskoye, 13th May

Dear Tatyana,

Please tell me why you’re convinced my daughters must be falling in love with Lyu? Till now I’ve regarded them as far too immature for love; Katya, after all, is really still a child. But since you’ve now drawn my attention to the matter, I can see that Lyu is dangerous: masculine, courageous, clever, interesting, eye-catching – everything that might impress a young girl. At this point, however, I must praise him for behaving in rather a reserved fashion towards my two little ones. Maybe he’s already engaged. I’ve certainly noticed Jessika’s admiration for him; whenever he speaks, her eyes fix on him, she is more talkative than normal and brimming with the loveliest ideas. I didn’t think there was anything bad in this; on the contrary, I’ve been delighted to see her so happy. Tatyana, if you wish to invite her and she wants to come, then I shan’t stand in the way. It may even be better if she does. My poor little Jessika; the idea that she’s in love with him! If he didn’t love her she would suffer, and perhaps even more if he did. No, he is not the man for her. He understands everything, but always remains sober-minded, never dropping his guard. He has no appreciation of trivial things or frivolity, or if he does, then it’s like collecting plants in a herbarium. He cannot give of himself, he only consumes. I believe him to be highly capable in many fields, and am sure he’ll be a terribly famous man one day. But whatever his future, my little girl would struggle to breathe in the thin, lofty air he needs.

What I find strange about this man is that he evidently has an active interest in all of us, he appears receptive to our qualities, he accepts the trust we place in him as a matter of course, and yet gives nothing of himself. It’s not that he isn’t open; every question you might put to him he answers candidly and thoroughly. It might even be misleading to call him withdrawn, for he talks rather a lot and always about things that are really important to him. And yet you never feel as if you know what he’s like inside. It’s already crossed my mind that there might be secrets in his life which compel him to be reserved, but it doesn’t bother me, as I’m sure that there’s nothing bad. Recently we were talking about lies. Lyu said that in certain circumstances lies were a weapon in life’s struggle, no worse than any other; only lying to oneself was contemptible. Velya said, ‘Lying to oneself? But I’d never believe me.’ Lyu gave a laugh of joy and I, too, couldn’t help laughing, but I felt duty-bound to tell Velya that it was a bad joke. ‘But we can’t crack better ones here,’ my boy said, ‘otherwise Katya won’t understand them.’ Well, what I really wanted to tell you was that I am truly convinced that Lyu would never lie to himself, and for me that’s the fundamental thing. The principle may be dangerous, but it’s reasonable for a person of importance.

Dear sister of my beloved husband, if I didn’t have the children around me, I could now imagine we were on our honeymoon. If only we never had to return to the city! Yegor has resumed playing the piano, for he cannot go a moment without being occupied, while I, who certainly can, listen to him and fall into a reverie. Do you recall the time when I called him my immortal? Sometimes, when I look at him now, I’m struck by the feeling that he’s become something else. It’s not the white hair, which has now overtaken the black, nor the deep shadows that often sit beneath his eyes, nor the harsh lines that darken his face. No, it’s something nameless that surrounds his entire being. Once I had to leap up all of a sudden and hurry away, because tears were pouring from my eyes, and in the bedroom I cried into the pillow, ‘My immortal! Oh, my immortal!’ I don’t consider it strange that there are mad people around, but it’s lamentable that even the most rational individuals can have fits of madness.<

br />

Yours, Lusinya

LYU TO KONSTANTIN

Kremskoye, 15th May

Dear Konstantin,

I might have predicted you’d react like this, but I hope you will have no cause to in the future. You make it sound as if I’ve come here to undertake a psychological study. You think I’m developing a keen sense of family life. You say I might just as well be visiting my aunt in Odessa and much more besides. What do you want? Did you expect me to pounce on my victim like a hungry cannibal, a hate-filled love rival or a cheated husband? We were agreed that we would not proceed like those fanatical ruffians who, when executing an assassination, seem to be more bent on disposing of their own lives than those of their targets. We wanted to achieve our goal without risking our lives, our freedom, maybe even our reputations, for we have more to achieve and we know that we are difficult to replace. If time were pressing, I would have acted differently, but the students’ trial only starts at the beginning of August, until which time the governor will be on holiday here. I therefore have three months, of which barely a fortnight has passed. I am taking a good look around, acquainting myself with the people, my surroundings, and waiting for an opportunity. Of course, I could have already killed the governor, had I so wished; I often find myself alone with him, in the house, as well as in the garden and the woods. But in that case I would have acted wrongly. At this moment in time when I am much valued, almost held in affection, and yet remain a stranger, suspicion could be raised against me. But in a few weeks I shall be as a member of the family, and suspicion will be out of the question. I believe I wrote recently that I sat beside him for a few minutes while he was sleeping. I gazed at the side of his face that was turned towards me – the broad, black eyebrows, a sign of great virility; the prominent aquiline nose; fire and nobility in every single one of his lines. Another key feature of his personality seems to be a passion tempered by genteel sensibility. What a wonderful man! As I watched him I thought how I should much rather make this head receptive to my thoughts, my opinions, than destroy it with a bullet. You must consider that I could avoid killing this man if I were to succeed in controlling, influencing him. But I will state right here and now that I regard this a very remote possibility. In small matters he’s like wax, in important ones like iron. If he is resolved on something, neither fear nor love can change his mind; at least, that’s how I see it at present.

The boy is different: he is so indolent that he is grateful if one stands up for him; one just needs to do it with discrimination. He is astonishingly open-minded. In no way does he appear to be a prisoner of tradition; something about him suggests there is nothing tying him to the past, his family or his motherland. I cannot help recalling an old fairy tale in which a parentless boy appears as the sun’s child. His golden-brown skin brings to mind this story too. In conversation with him I virtually speak my mind; he is so unprejudiced that it doesn’t even occur to him to wonder how I could have taken a post with his father given the views I hold. He appears to find it only natural that a man of reason can think as I do, while also playing any role that suits his taste and is useful to get him ahead. I like the boy and I’m most glad not to have to harm him. Katya thinks like her brother, maybe in part out of love for him. For a girl, she is highly intelligent and insightful, but no matter how sensibly she talks, she is still like a sweet little bird chirruping on a perch. I find this enchanting about her.

Konstantin, do not reproach me again. If there were accusations to be made I should level them myself, and for this reason no one else has the right to do so.

Lyu

JESSIKA TO TATYANA

Kremskoye, 15th May

Oh, most gracious Auntie, you have invited me to visit you! I kiss your hand in gratitude. And I may even come when you’re not expecting it. But, dearest Auntie, do you not know that I have duties here? I cannot leave just like that. There is a household to be run and, as you know, even the best servants need to be inspired by a higher being. I pity that poor cook who, with our fivefold whimsies, would have no backup if I were to leave. Papa adores stuffed tomatoes, but not tomato sauce, which Mama is very fond of; and whereas Velya has a passion for tomatoes in salad, Katya only eats them raw. Katya won’t eat sweet rice, Papa won’t touch spicy rice and I don’t like rice pudding. None of us eats cabbage, but we want green vegetables every day. I could go on like this for pages. No cook could possibly keep all that in her head, and ours cannot read. If I went away, Mama would have to think of everything – for it would never occur to Katya – and I’d be very sorry. She spends her days wandering around the house, and is pleased to have her husband to herself, as well as in safety. Now is not the time to burden her with silly everyday concerns.

You’ll think I’m just an insignificant little girl! But they’d soon notice if they weren’t served their cup of tea or coffee with precisely the amount of sugar and milk or lemon that each of them likes, or if the orange slices did not fly onto the dish thinly cut and without pips, as they are used to, or if the pencils, scissors and parasols that they lose or misplace were not found by me at just the right moment! This is what I do! Why don’t you come and see for yourself just how indispensable I am?

If you now think that I ought to be rewarded and compensated, Aunt Tatyana, then send me some purple batiste for a blouse and matching trim and lace. I’ve nothing here light enough to wear in this heat. You have the finest taste of anybody, my lovely Auntie, so please acquire these things for me.

Your grateful Jessika

VELYA TO PETER

Kremskoye, 17th May

Dear Peter,

I was wrong: au fond Lyu is a revolutionary; it’s just that there’s something which makes his opinions tower above average ones. How can I make you comprehend this, my dear megatherium? He thinks, while at the same time standing above his thoughts. He doesn’t regard the things he thinks and wishes for as the ultimate, the absolute. This is why he also stands aside from party politics; he gazes out over the parties. He says that the new generation is right vis-à-vis the older one, although viewed in isolation it is almost less in the right than the older generation. You won’t understand this of course because you lack self-irony, both the concept of it and the trait itself. Your lot have no idea how amusing it is when you get worked up about how degenerate the old culture has become and yet have not the faintest idea of what culture actually means. Don’t get worked up, don’t start roaring, you old dinosaur, I’m absolutely on your side. My father is priceless. He regards Lyu as a terribly nice, intelligent and entertaining man; his sharp eye goes no further. He cannot conceive of the idea that a man in honest clothing, who behaves politely and refrains from contradicting him, could possibly move outside of his system. Mama is much less, how should I put it, wrapped up in herself. She, at least, can clearly see that she’s a long way from understanding every facet of Lyu’s character; she senses something unfamiliar, even though she cannot apprehend it. Recently she told him that the position he occupies in our house was not commensurate with his talents, knowledge and efficiency. Nor was the remuneration, she added; he should never have accepted it. Lyu said he’d hoped that being a private secretary would afford him the free time he needs to complete a philosophical work, which is his next aim. Mama turned a deep shade of red and said surely he must be disappointed, as we were forever making demands of him. I think Lyu had completely forgotten that he’s here to intercept bombs and murderers, while Mama thinks he’s wearing himself out with this difficult to define activity. Since then she’s often invited him to retire to his room and work, and she has a tendency to think Papa’s being very demanding when he wishes to dictate the occasional letter to him in his spare time. He could easily get himself a typewriter, she said. You could hardly say that Mama exploits people.

We are currently urging father to buy a motorcar, and he’s very close to doing so. At the dinner table we’re always discussing the last automobile race and debating whether it’s cheaper with petrol or electricity.

Lyu wondered whether we might not wait until we could acquire a navigable aircraft. Papa was most taken with the idea, and once he’d calculated the costs of such a purchase, a motorcar seemed terribly ordinary and petit bourgeois by comparison. Lyu is not a bit musical. He claims music is a primitive art form, at least the music we know up till now. One day it could possibly be different; Richard Wagner has given vague intimations of this. But he says the musical offerings in our family are primitive. I think he’s absolutely right, especially as far as Papa is concerned. His playing is beautiful, but in the same way that the forest rustles or the wind whooshes: there’s something demonic about it. Obsession is not a sign of culture, however. On the other hand, Lyu seems to have a lot of time for the primitive. He thinks that Jessika’s voice sounds like the red of dawn emerging in the pallid first light of the east. I think Jessika has a good voice too, to me it sounds like a harp, but I’ve never really had much time for singing in itself; after all, music really begins with the symphony. Do not imagine for a moment that you’re a superior being because you’re unmusical. With you it’s a vacuum.

Velya

KATYA TO TATYANA

Kremskoye, 17th May

Dear Auntie,

Jessika forgot to ask you to buy for us the score of Tristan und Isolde, or have someone else do it. Papa is against the idea; he says musical scores can be borrowed too! Does that sort of thing exist? Oh, please don’t bother finding out; borrowing books from a lending library is rather vulgar, and scores are books, aren’t they? Deep down Papa is just annoyed that we’re interested in Wagner; he’s so biased. He doesn’t even want to get to know Wagner; he’s determined to find him dreadful from the outset. Well, if Wagner had lived a few hundred years ago and composed church music like Palestrina – oh, I know it sounds stupid, but I’ve written it now, and you understand what I’m saying. Of course Beethoven’s songs to his distant lover, which Papa always sings, are beautiful, but they’re not an expression of our time and our lives. Anyway, Auntie Tatyana, you’ll send us Tristan und Isolde, won’t you? Please do so quickly. Peter can go and get it.

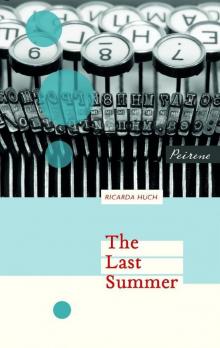

The Last Summer

The Last Summer